By Corey Lacey, Ph.D., ISA Environmental Policy Manager

In late August, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released the final Herbicide Strategy. In their own words, this was an “unprecedented step in protecting over 900 federally endangered and threatened (listed) species from the potential impacts of herbicides.” Unfortunately, the strategy is also an unprecedented first step in overhauling established U.S. pesticide policy – requiring Illinois farmers to rethink how they use pesticides over the coming years.

Question: Why are the changes coming?

In recent years, the EPA has come under a multitude of lawsuits about pesticides and protection of listed species. This culminated in 2023, when the EPA bent to legal pressure, settling a lawsuit brought by the Center for Biological Diversity. It committed to come into compliance with its Endangered Species Act obligations.

Question: What is the Endangered Species Act?

The Endangered Species Act is a federal law that, among other things, requires federal agencies to protect listed species when they take official agency actions. The registration or re-registration of pesticide labels for use is one example of an agency action. In the 2023 settlement, the EPA admitted that it had not been meeting its ESA obligations for decades. As a result, it now must come into compliance rapidly.

Question: How will the final Herbicide Strategy impact Illinois farmers?

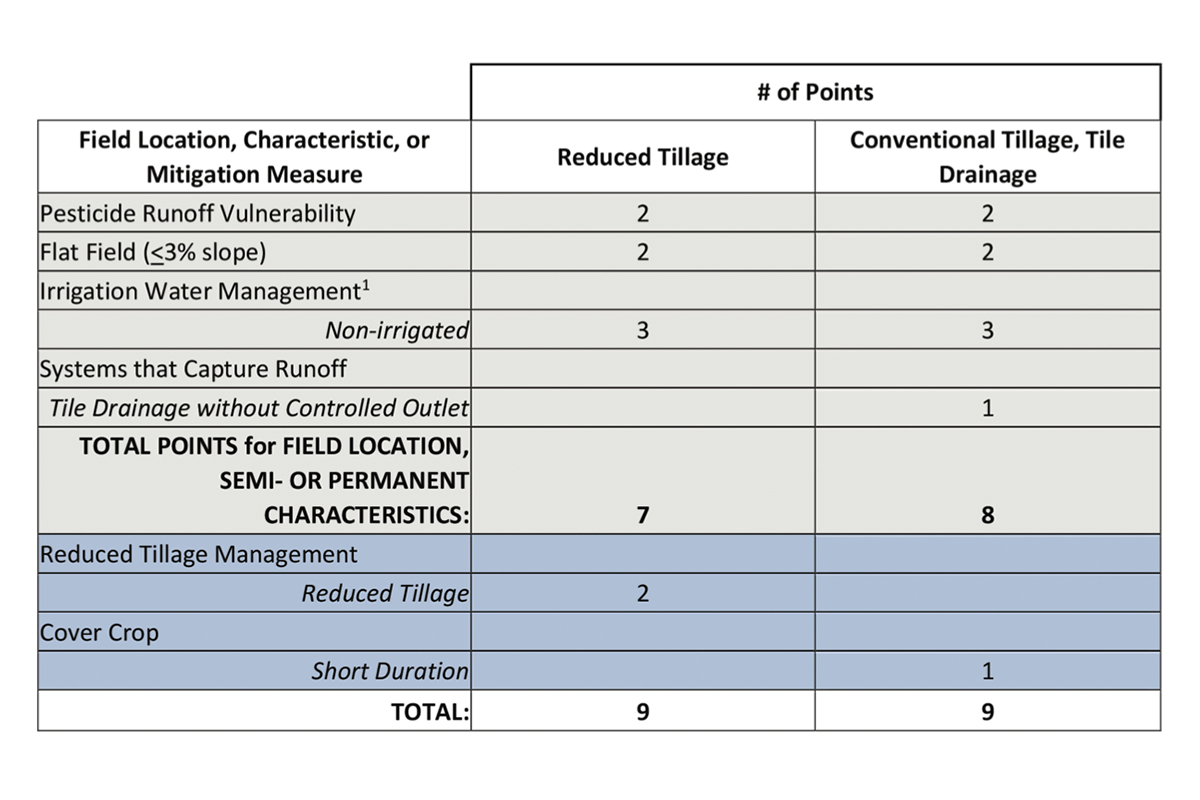

The final Herbicide Strategy does not create immediate regulation but sets the framework for which the EPA will evaluate future pesticide labels. The framework requires farmers to meet mitigation requirements to limit runoff and drift concerns from specific fields. For runoff mitigation, individual pesticides will have specific “mitigation point requirements” that must be met to allow applications. In the example scenarios provided by the EPA (Table 1), some of these points may be met by existing field conditions such as tile drainage, field locations, or low slope. However, even when these situations are met, farmers will need to adopt other practices from a mitigation list. In some cases, this will create a pseudo-mandatory adoption of conservation practices such as cover crops and no-till.

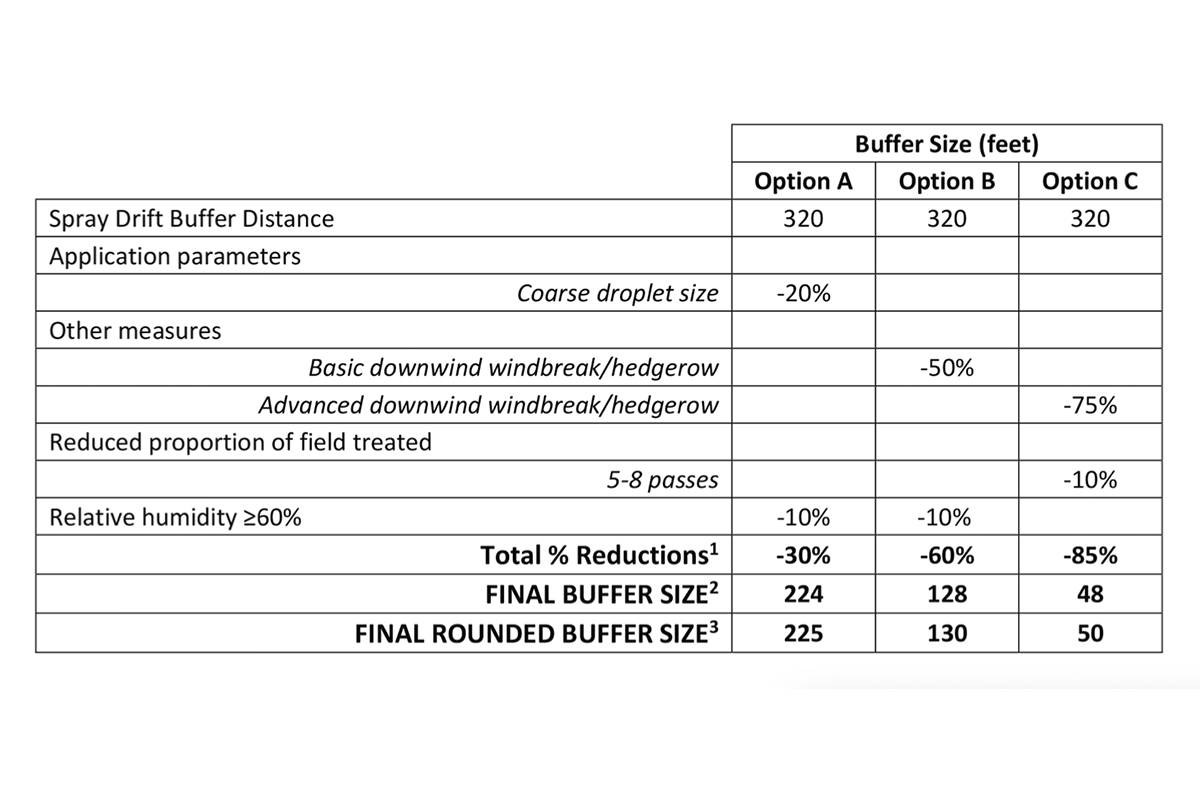

To meet drift concerns, Illinois farmers could be required to implement drift buffers of up to 320 feet. However, drift mitigation measures could allow farmers to reduce buffer size by adopting certain conservation practices such as: increasing droplet size, lowering boom height, planting hedgerows/windbreaks, or reducing the area of a field being applied. Table 2 runs through three scenarios presented by EPA in which Illinois farmers could reduce the buffer size from 320 feet to 225 (Option A), 130 (Option B), or 50 (Option C).

The final strategy is an improvement over the draft strategy the agency released last year. For example, requirements for many Illinois farmers were eased because of permanent field features that reduce runoff risk. It’s also clear that the EPA listened to some concerns from Illinois farmers. For example, based on the draft language, the Herbicide Strategy would have limited the ability of tile-drained fields to meet mitigation requirements. In a reversal, based on farmer feedback, the Final Strategy made tile drainage a mitigation practice – reflecting the science that drainage reduces runoff – easing the regulatory burden on these fields.

However, Illinois soybean farmers should be aware of challenges to the practicality of the proposed mitigation measures. Often, meeting requirements would involve costly physical changes to fields. This could include adoption practices that reduce yields, add buffer zones, and take land out of production. Additionally, to meet court-ordered timelines, the EPA is bypassing sound science, opting to force mitigation requirements on farmers without establishing an actual danger to endangered species. This could lead farmers to adopt expensive changes unnecessarily.

To be among the first to know about potential changes to pesticide regulations and other pressing issues, consider becoming a member of Illinois Soybean Growers. Your membership dollars directly support efforts to advocate for farm-friendly pesticide policy in Washington, D.C. and Springfield.

Table 1: Non-irrigated soybean and corn on flat land, non-sandy soil Adapted From: https://www.regulations.gov/document/EPA-HQ-OPP-2023-0365-1139

Table 2: Aerial use of pesticides on corn and Soybean grown in Illinois Adapted From: https://www.regulations.gov/document/EPA-HQ-OPP-2023-0365-1139

Recent Articles

ISA recently traveled to Indonesia to explore growth potential for U.S. soy's No. 4 trade partner.

By IL Field & Bean Team