By Jonathan Coppess, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Now that the annual August recess in Congress has arrived, the eff ort to reauthorize the Farm Bill remains at an impasse, and reauthorization this year looks increasingly unlikely. The challenges for the Farm Bill are becoming all too familiar and increasingly problematic—budget challenges, partisan conflicts over food assistance to low-income households and demands to increase farm program payments. The House Committee on Agriculture reported a Farm Bill in May, largely along party lines and unlikely to be considered on the House floor (see H.R. 8467; House Agriculture Committee, Farm Bill 2024). The Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry has not produced any legislation or made any forward progress, but the Chair and Ranking Member have each released framework proposals (see Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry, Majority News, May 1, 2024 and Minority News, June 11, 2024). Let’s take a look at the issues facing the Farm Bill from a soybean perspective.

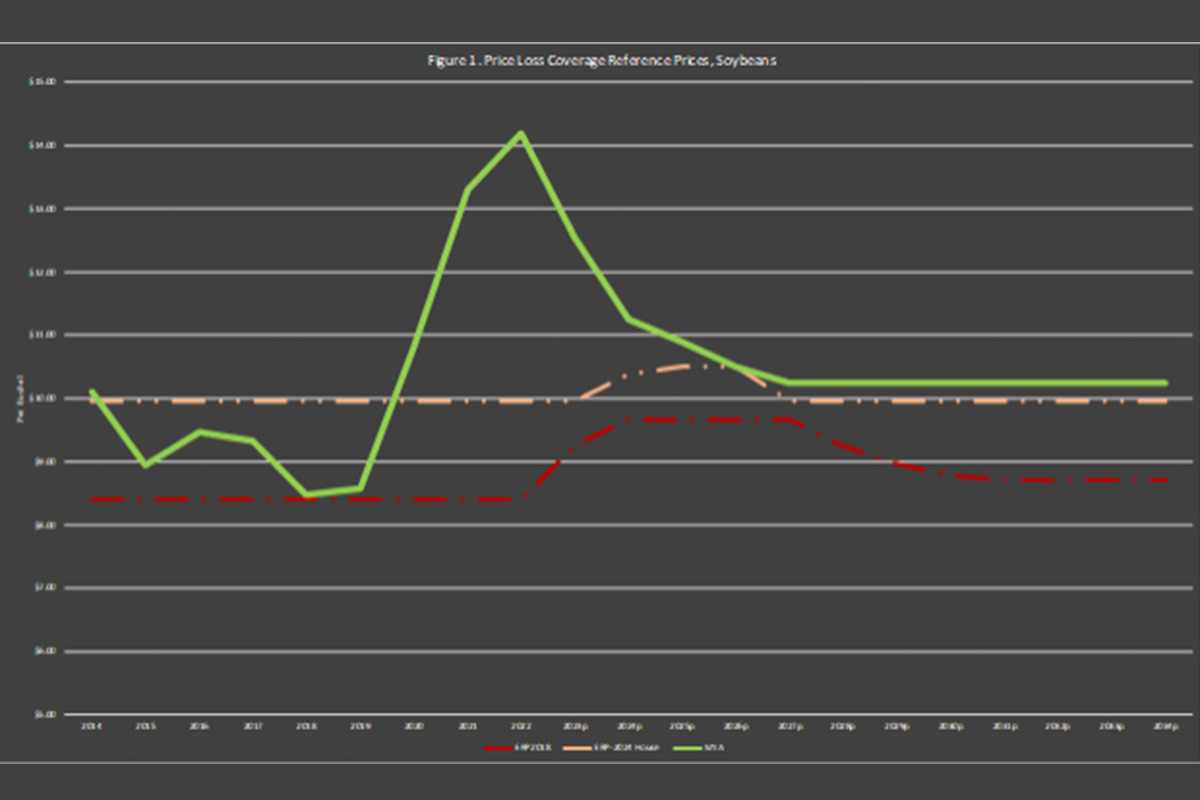

At the core of the Farm Bill impasse is a demand from farm groups to increase the reference prices that are the thresholds for base acre payments through the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) program and are included in the Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) program’s calculations. PLC triggers a payment on 85 percent of the base acres for the crop whenever the 12-month marketing year average (MYA) price for the crop is below the eff ective reference price (ERP). The 2018 Farm Bill included the ERP calculation by which the statutory reference price (for soybeans, $8.40 per bushel) can be increased up to 115 percent whenever 85 percent of the previous five-year Olympic moving average (drop the highest and lowest years) is greater than the statutory reference price. For soybeans, the reference price for the 2023 marketing year (ending this month) will automatically increase to $9.26 per bushel and will reach $9.65 per bushel for 2024 (see, farmdoc daily, October 5, 2023). The PLC problem for soybeans is that the MYA price has not fallen below the reference price threshold and is not projected to do so. The House Farm Bill proposes increasing the soybean statutory reference price by 19 percent to $10 per bushel. Figure 1 (see page 21) illustrates the PLC eff ective reference prices as compared to the MYA prices (projections by CBO) under current law from the 2018 Farm Bill and the House Agriculture Committee’s Farm Bill. Figure 1 applies both reference prices back to 2014 when the PLC program was first enacted.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

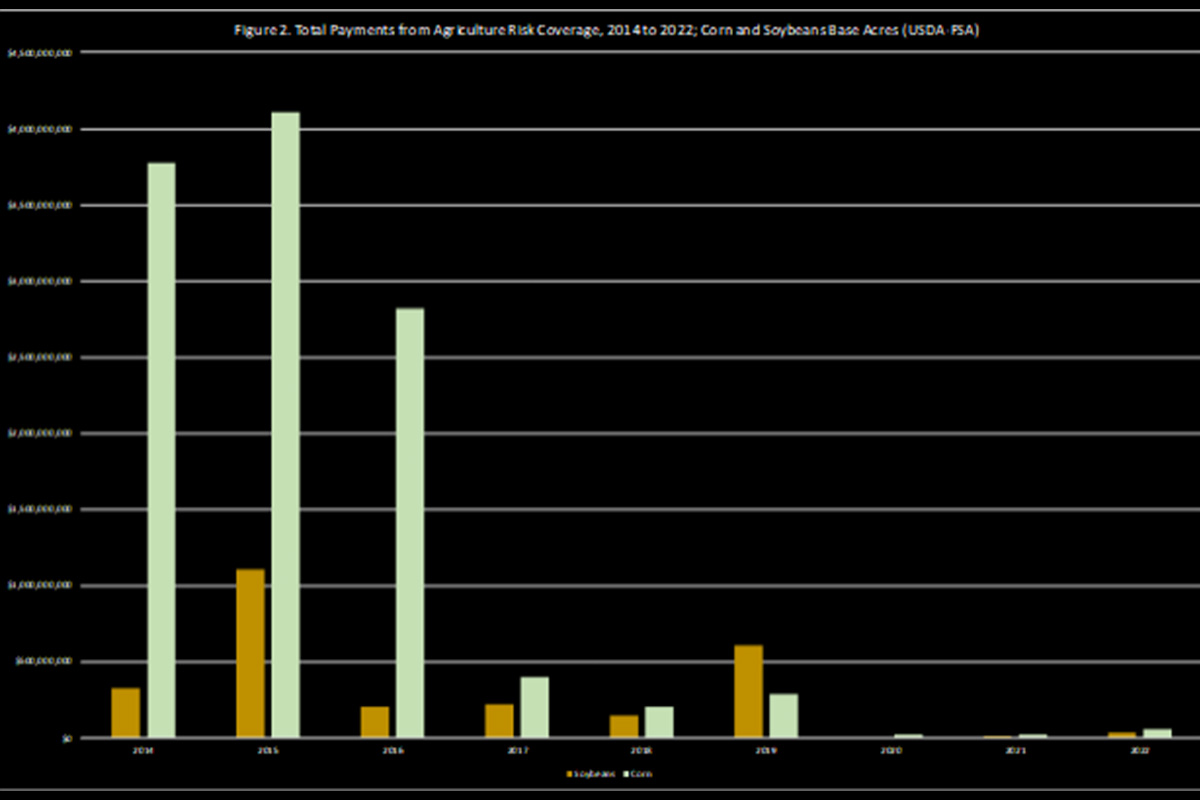

As is clear in Figure 1, PLC has not triggered payments for soybean base acres since it was created in 2014. Neither the increase under current law nor under the House Farm Bill is likely to trigger PLC payments for soybeans base. By comparison, the ARC program has made payments on soybean base. Figure 2 illustrates the total payments for soybean base acres as reported by the Farm Service Agency since 2014. It includes the payments for corn base acres as well. Comparing ARC and PLC helps clarify why most farmers with soybean base acres elect to enroll them in the ARC program over PLC. It seems unlikely that the House Farm Bill would change that, in spite of the increase to the soybean reference price.

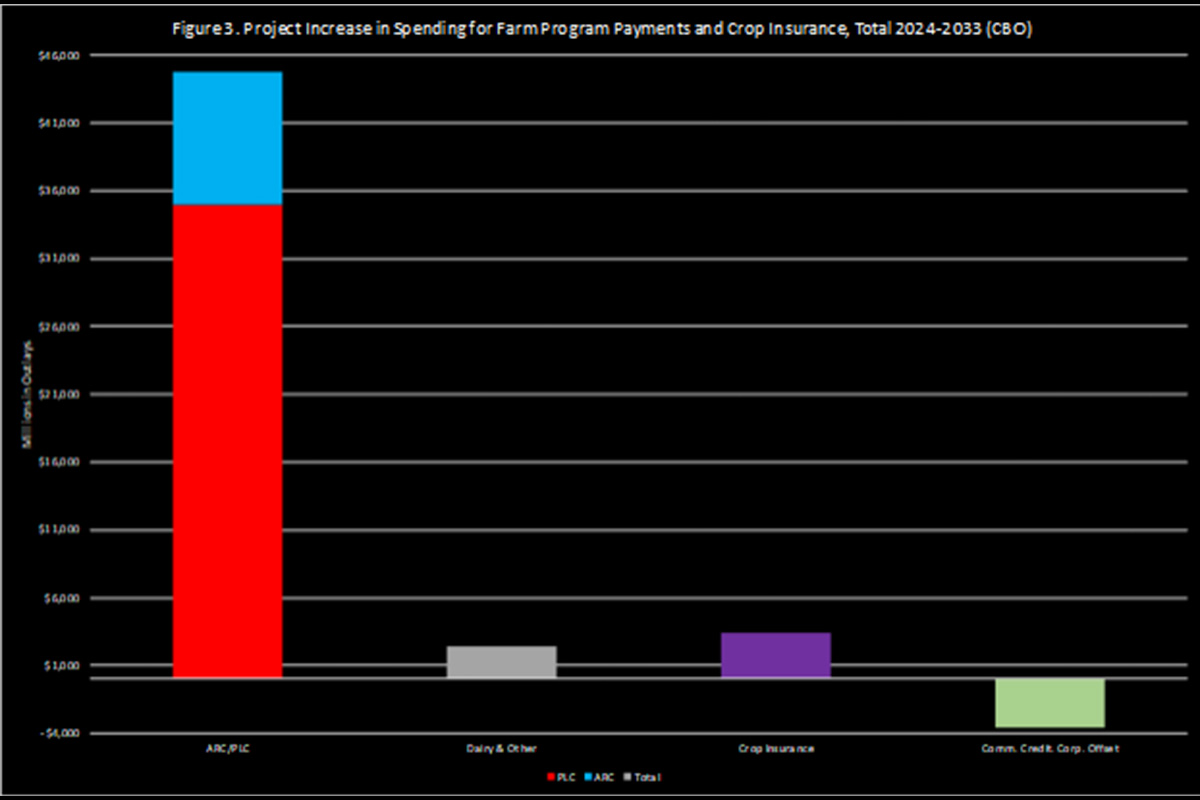

One of the primary challenges for the Farm Bill is the overall cost for increasing reference prices and other payment thresholds in farm programs. Congress created the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in 1974 to operate as a non-partisan, unaffiliated resource for objective analysis on budget and economic matters. Congress requires CBO to project 10-year spending estimates to create an annual baseline, as well as requiring CBO to score legislative changes against the baseline over one-, five-, and 10-year budget windows regardless of the length of the authorization (2 U.S.C. §639; 2 U.S.C. §907; CBO, April 18, 2023 (cost estimates); and April 18, 2023 (baseline); see also, farmdoc daily, June 6, 2024; March 23, 2023; February 13, 2020; July 18, 2019; April 18, 2019; November 29, 2018). Increases in spending above the baseline projections are required by law to be offset with reductions in spending from other programs or increases in revenue. The 118th Congress, moreover, added a provision known as “CUTGO” that prohibits consideration of any legislation that increases mandatory spending within either a six-year or 11-year window (House, January 10, 2023, Rule XXI, clause 10; Heniff, CRS, May 9, 2023). CBO recently released the official cost estimate for the Farm Bill reported by the House Agriculture Committee in May (CBO, Aug. 2, 2024). Figure 3 illustrates the total 10-year cost estimate for the House Farm Bill’s changes for farm programs and crop insurance as projected by CBO. CBO projected that the total additional costs of farm programs and crop insurance, without offsets, would exceed $50 billion over 10 years. The increase in reference prices for PLC will cost nearly $35 billion, while the proposed spending offset from the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) is worth only $3.6 billion (see farmdoc daily, Aug. 8, 2024).

“The House Farm Bill proposes increasing the soybean statutory reference price by 19 percent to $10 per bushel.”

The budget challenges in the House Farm Bill are magnified by continued partisan fights over the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides aid to low-income households for the purchase of food. SNAP serves over 40 million Americans, on average, every month. The House Farm Bill proposes changes to the SNAP calculation that CBO projects would reduce the program by more than $30 billion over 10 years, though the House does propose to spend $10 billion on some aspects of the food assistance programs. This has been tried before and has created substantial problems for Farm Bill reauthorization. Both the 2014 and 2018 Farm Bills were nearly derailed by partisan fighting over SNAP in the House of Representatives, and it does not help 2024 reauthorization. More problematic, the House Farm Bill in 2024 marks the third straight attack on this critical coalitional partnership that is vital to moving legislation through Congress and having it signed into law.

In conclusion, the House Agriculture Committee advanced legislation to reauthorize the Farm Bill in May, but the bill has almost no chance on the House floor. The bill suffers from significant partisan conflict over cutting food assistance to low-income households, as well as budget challenges for the proposal to increase farm program payments. The effort to increase program payments to farmers not only complicates the coalitional dynamics in a bill that also cuts food assistance, but the increases in payments are severely disparate among farmers in different regions of the country with the largest payments benefiting farmers in the South (see farmdoc daily, May 21, 2024). The Senate Agriculture Committee has had to save the Farm Bill from these same problems in the House in both 2014 and 2018, but this time around, the disagreements over payments and policies have prevented that committee from making any progress on a Farm Bill. With the legislative calendar quickly closing in an election year, the likelihood of reauthorization has become nearly nonexistent. It is likely that a lame duck session after the election will simply extend the 2018 Farm Bill for another year and hand off the challenges to a new Congress.

Recent Articles

ISA's new Agronomy Farm is a nearly 98-acre site designed to turn checkoff-funded research into practical, field-ready insights for Illinois farmers.

By Abigail Peterson, CCA, ISA Director of Agronomy