One of the most overlooked characteristics of soil is actually the easiest part of the soil for you to see. In fact, every time you walk out into a field, you have direct contact with it—it’s the soil surface. And, while most farmers are happy to dig into it to check their furrow closure and keep an eye out for standing water, not too many know just what processes affect how that soil surface behaves. For example, what happens when it rains or dries or has the weight of equipment driven over top of it?

Soil is made up of mineral particles of different sizes—clay is the smallest, followed by silt. Both are too small to see an individual particle with the naked eye. Sand is the largest mineral particle, up to 2 mm in diameter. Each soil has a different ratio of those three particles, giving it a particular soil texture. Most soils in Illinois are somewhat close to silt loam or silty clay loam, though areas near rivers have much higher sand content. All of that might be just a refresher on things you already knew. But what many farmers might not realize is that for the soil surface, an even more important aspect is how those different mineral particles are linked to each other. Do they lightly connect but break apart with the slightest wind or water forces? Or better yet, are those particles tightly glued together into large structures, which we call aggregates?

It might seem a little counterintuitive to want soil particles that stick together. After all, we generally talk about wanting good soil tilth, which is the physical condition of the soil and how suitable soil is for planting and growing crops. Often, discussion of soil tilth is connected with good seedsoil contact and sometimes considered in relationship to soil tillage. So wouldn’t it make sense that we want soils to break apart so the particles can get better contact with the seed in the furrow? Yes, that’s definitely true for soil clods that form after soils are tilled or disturbed. We want those soils to crumble. But the goal is for those soils to crumble into the soil aggregates and not into the individual soil particles. In fact, this might be one of the biggest issues a farmer can face with soil structure. That’s because if those individual soil particles break apart, they can cause all sorts of issues compared to soils that have particles that stay glued in larger soil aggregates.

Mother Nature always causes issues, but they seem to be showing up at higher rates in recent years. Farmers face more frequent heavy rainfall events that interfere with planting and other field operations. Heavy rainfalls of 2 inches in a single day or even in a few hours can dump over 54,000 gallons of water per acre. The aggregation of soils plays the biggest role in what happens to that water when it hits the soil surface.

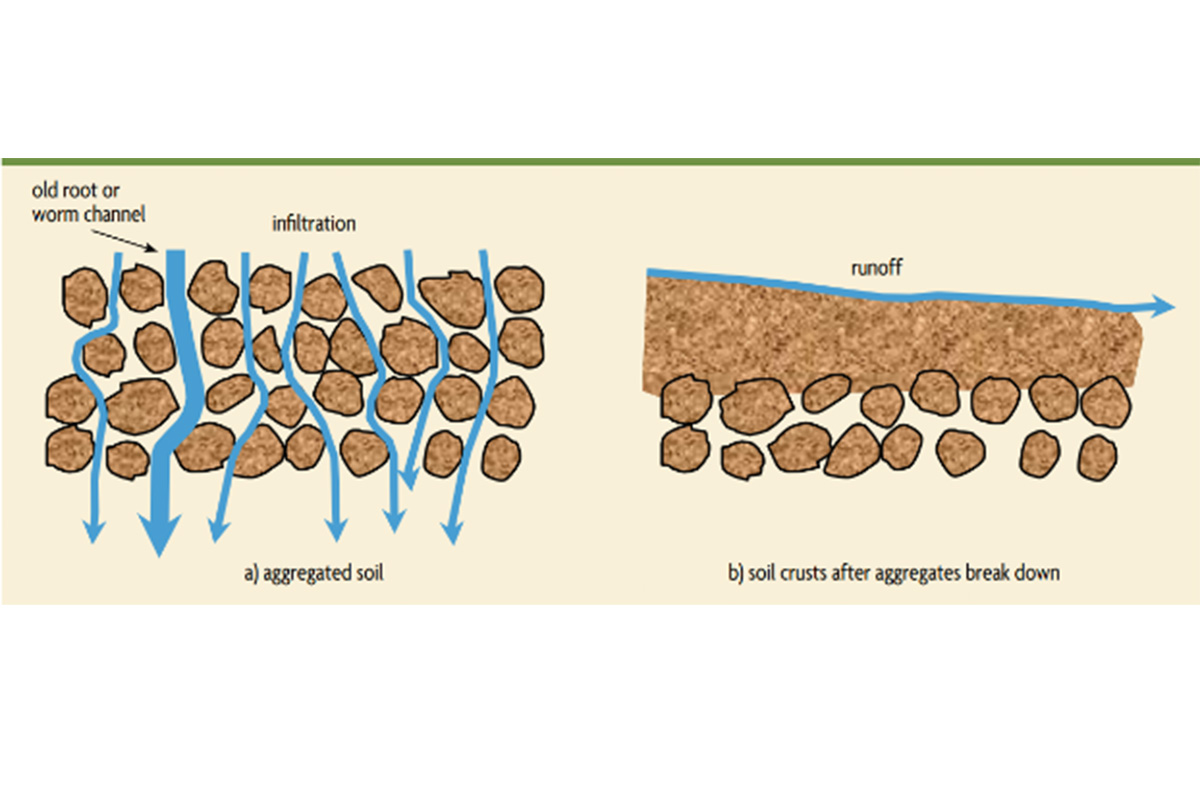

When soil particles are glued together into strong and stable soil aggregates, it creates more open pore space within the soil. That open pore space is vital for water to be able to infiltrate and be absorbed into the soil. When soils have few glues or the glues are weak, soil aggregates might barely exist and break apart easily. This can happen just from the force of a raindrop falling and hitting bare soil. When those particles break loose, they are now free to move in the water. They may leave in runoff, carrying phosphorus and organic matter alongside those soil particles. In the best case scenario, they stay in the field. But this can exacerbate the existing problem. Those loose soil particles still need to go somewhere, and they settle out on the soil surface or maybe move down into the few open pore spaces available to them. This can plug the few existing open pore spaces at the soil surface. It can also lead to problems with soil crusting. Depending on the time of year, it can cause emergence issues in the spring if the crusting is bad enough.

Figure 2.6. Changes in soil surface and water-flow pattern when seals and crusts develop.

Soil is made up of mineral particles of different sizes—clay is the smallest, followed by silt. Both of these are too small for the naked eye to see. Sand is the largest mineral particle at up to 2 mm in diameter. Photo Credit: Jeff O’Connor

Not only does soil aggregation benefit water infiltration and reduce erosion, but it can have potential influences on crop yields, particularly in years with extreme weather patterns. We’ve already mentioned the heavy rainfall events that seem to be more and more common. Yet most farmers would love to have a workaround so they can get out and plant quickly after a rain event without risking compaction. We saw that this spring. Rains kept planters out of the field much later than what is comfortable for most. The key to preventing compaction is to always avoid driving on wet soils. In well-aggregated soils, while compaction can still be an issue, the risky timeframe is narrowed. This is because well-aggregated soil allows water to move deeper into the soil profile rather than remaining on the soil surface. Soils with poor aggregation, loose soil particles or plugged particles or pore spaces tend to suffer from trapped water. This creates the worst compaction conditions when heavy equipment is driven over those wet soils. Even in drought conditions such as those farmers faced in 2023 and, to a greater extent, in 2012, good soil aggregation might help reduce yield losses. The open pores and increased water infiltration (when it does rain) help to increase water storage and availability. That means crops grown in those soils might be able to hold off against drought stress for an extended period of time.

So where do those glues that hold soil aggregates together come from? They come from plant roots and soil microbes—bacteria produce polysaccharides and fungal hyphae that help to enmesh soil particles together. It’s the living organisms within the soil that help provide the cement to assist in building the soil structure.

Those glues are also primarily composed of soil organic matter, so building soil aggregates not only creates more carbon storage within the soil but also physically protects carbon within the aggregates from degradation or further decomposition.

The keys to building soil aggregates are to feed the soil biology and protect the aggregates so they remain intact.

Minimizing soil disturbance is key, as tillage not only destroys existing soil aggregates but also reduces fungal populations that are key contributors to building soil aggregates in the first place. Soils that are frequently tilled typically have very poor aggregation. This leads to issues with poor water infiltration, runoff and erosion. It also makes soil more susceptible to compaction when the weather doesn’t cooperate. Reduced tillage or strip till can still allow for good aggregate so long as they are paired with other practices that feed the soil biology. It’s important to give soil microbes as diverse a diet as possible, whether through diverse crop rotations (even if simply adding wheat to a corn-soy rotation) or branching into cover crops. Advanced methods could include grazing cover crops and integrating livestock or just using a multi-species cover crop mix.

Building soil aggregates takes time, but even just a few years of reducing tillage and adopting cover crops can improve water infiltration and reduce other issues resulting from poor soil aggregation.

To learn more about strategies for improving soil aggregate stability, you can download a PDF copy of “Building Soils For Better Crops Fourth Edition” by Fred Magdoff and Harold Van Es, published by USDA’s Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE). To do so, visit https://www.sare.org/resources/building-soils-for-better-crops/

Recent Articles

TikTok sensation Jackson Laux, age 9, partners with John Deere to inspire agriculture's future.

By IL Field & Bean Team

From cutting-edge research to hands-on support, discover the vital role Extension plays in improving farm operations and advancing Illinois agriculture.

By Talon Becker, Commercial Agriculture Specialist, University of Illinois Extension